Execution

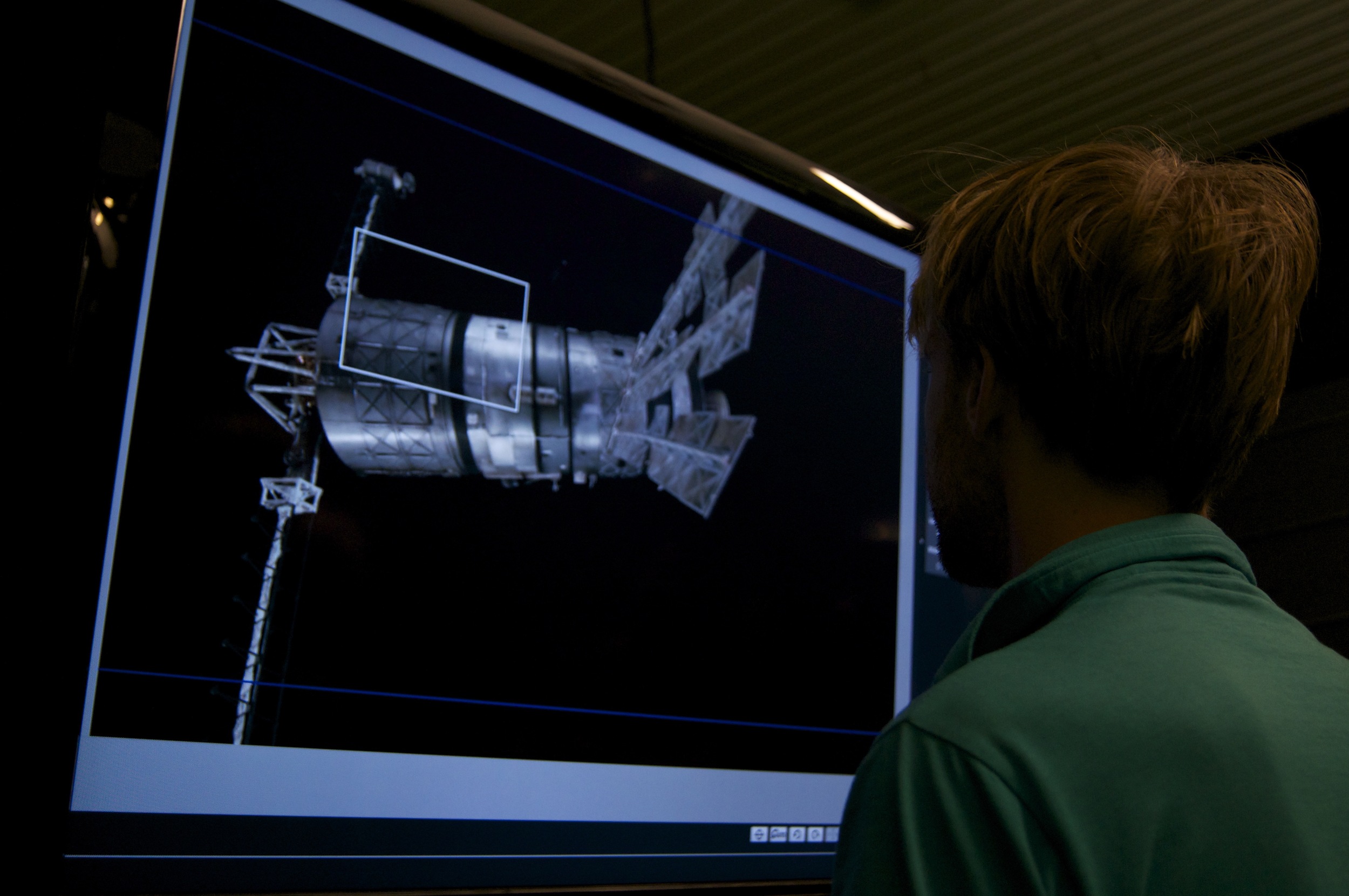

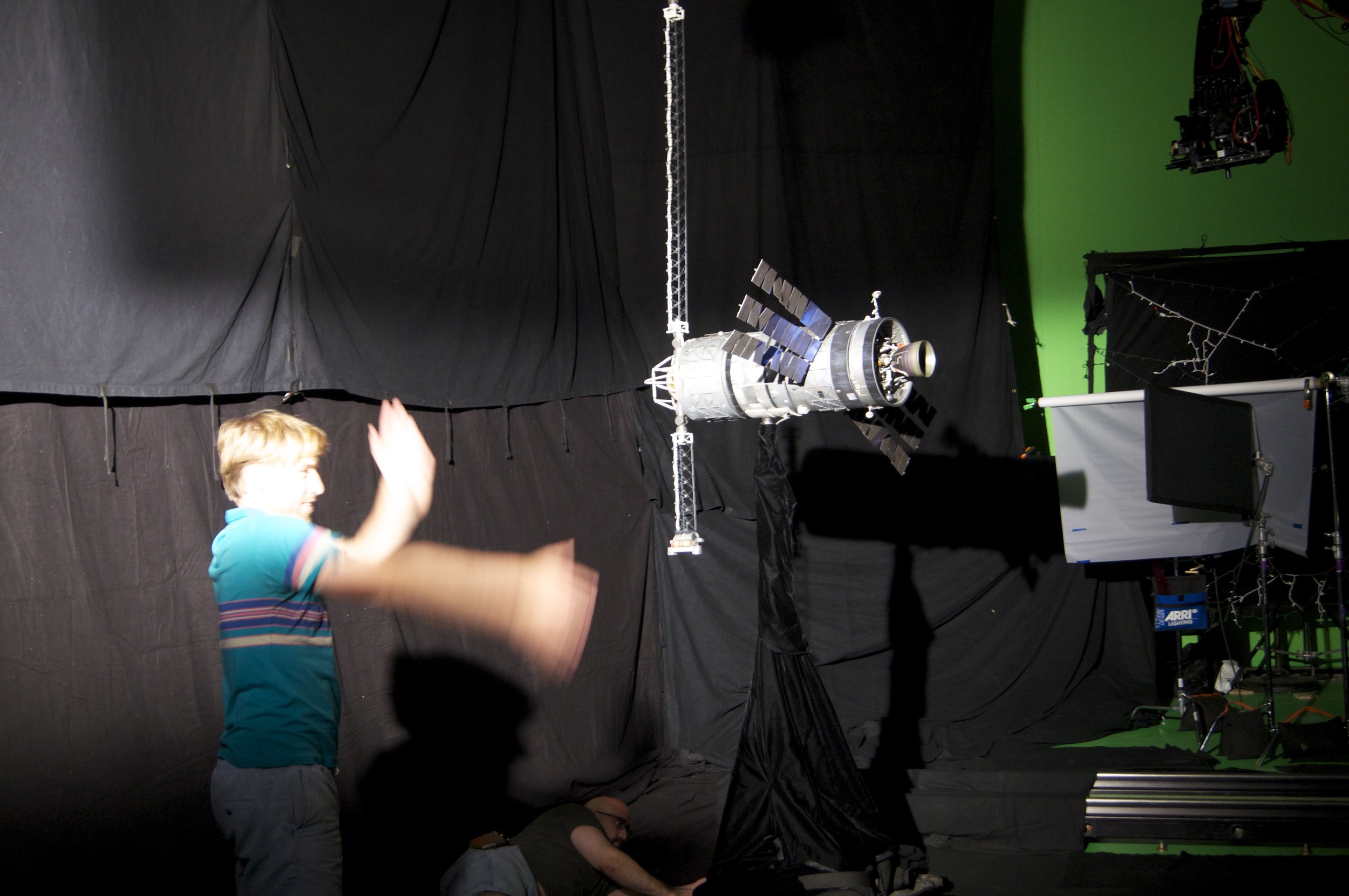

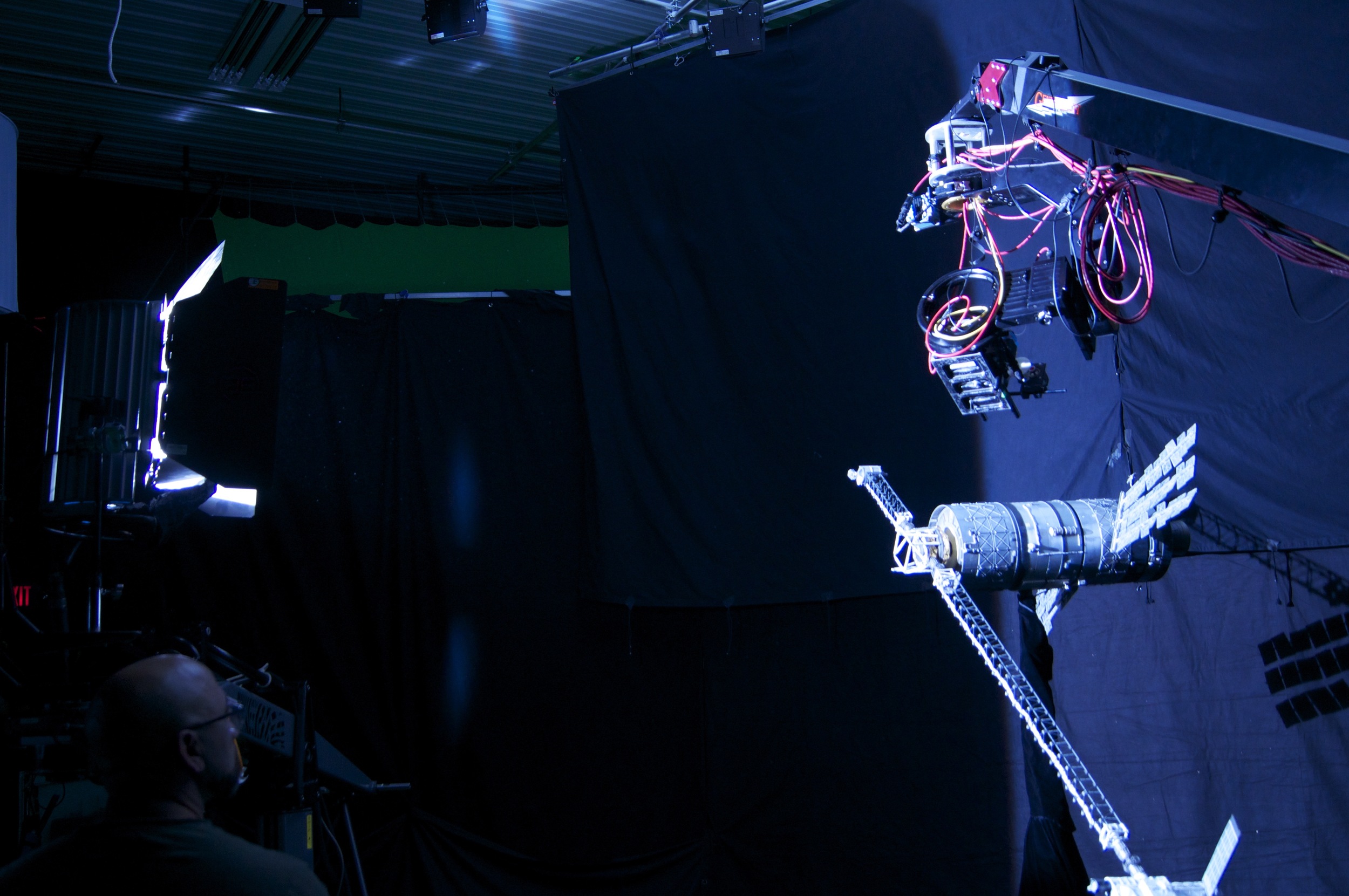

Because the character is isolated in unknown territory -- there’d be no camera crew out there -- I wanted the outer space shots to feel subjective, from Stanaforth’s perspective or imagination. So it was important to me to create a visceral, tactile feel to the models and to space itself, and I thought we could achieve that using practical models instead of computer graphics.

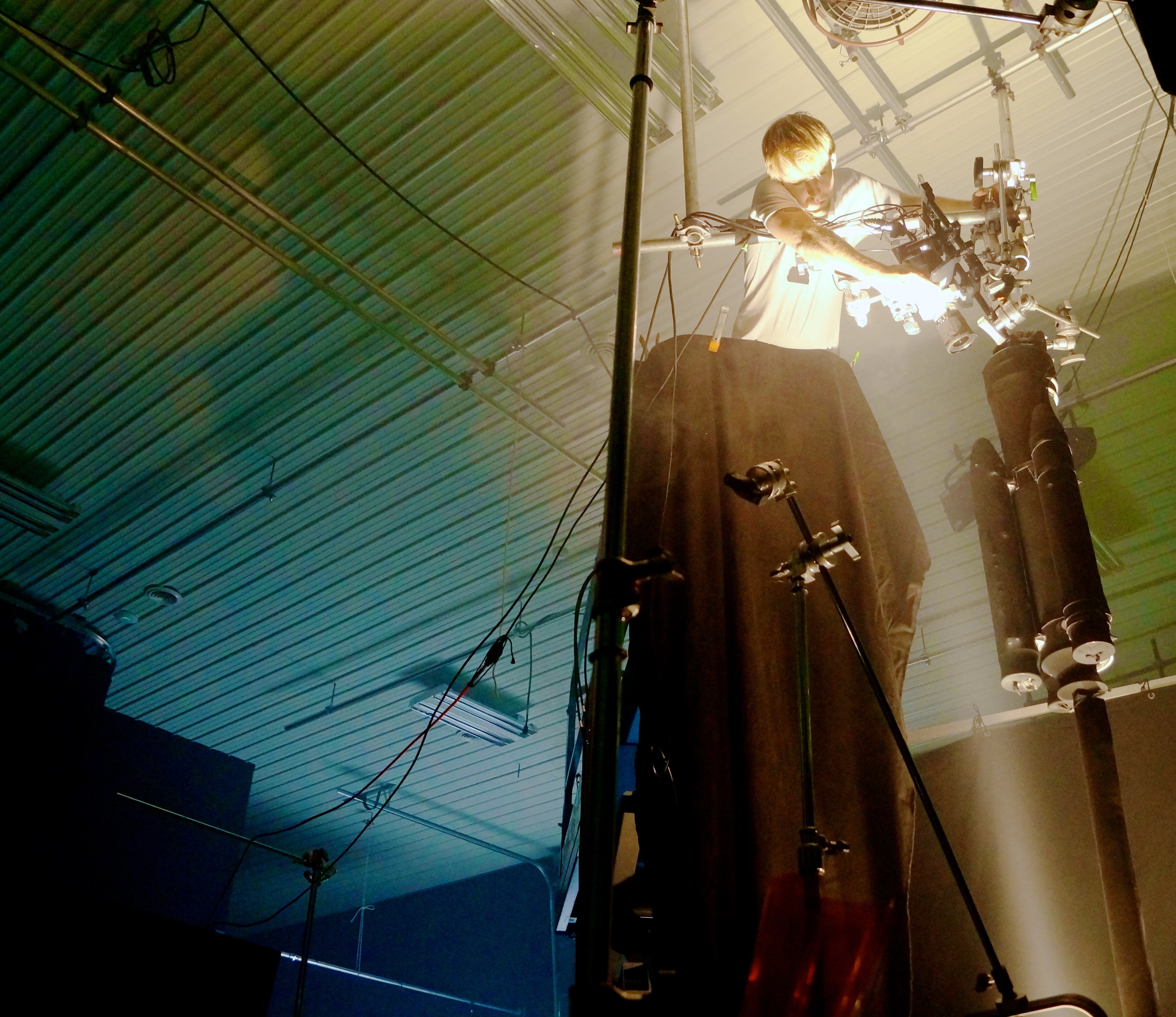

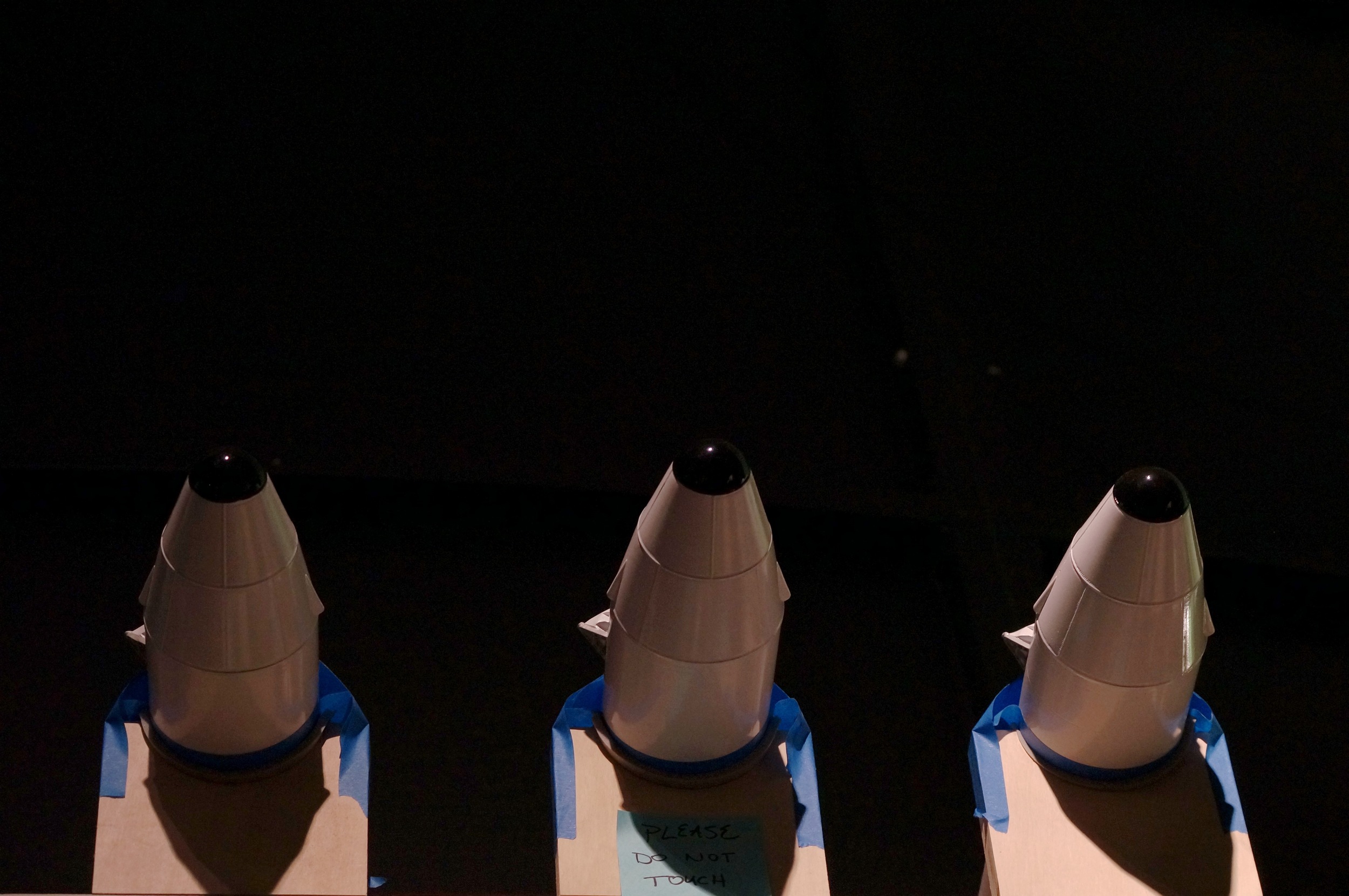

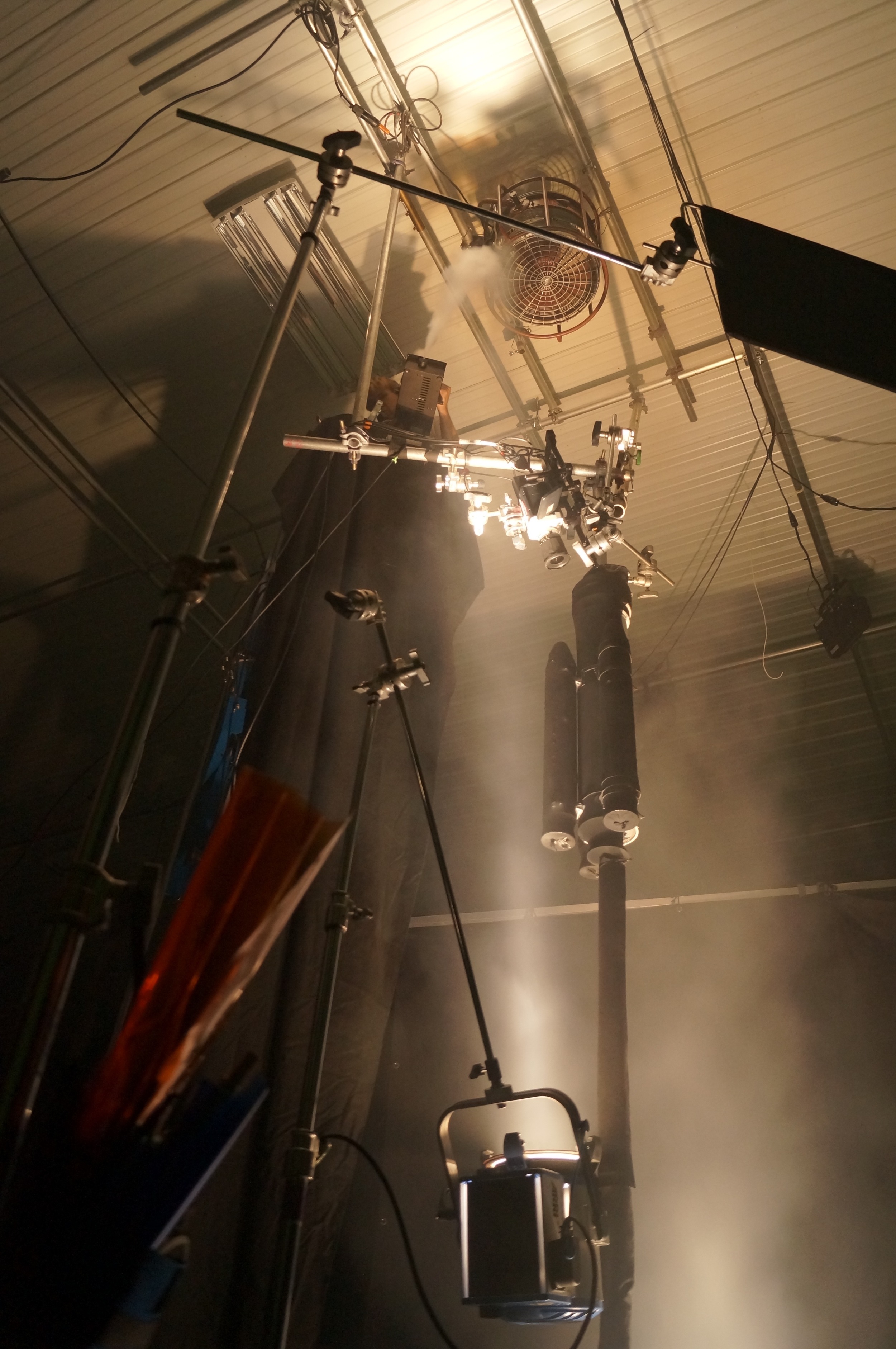

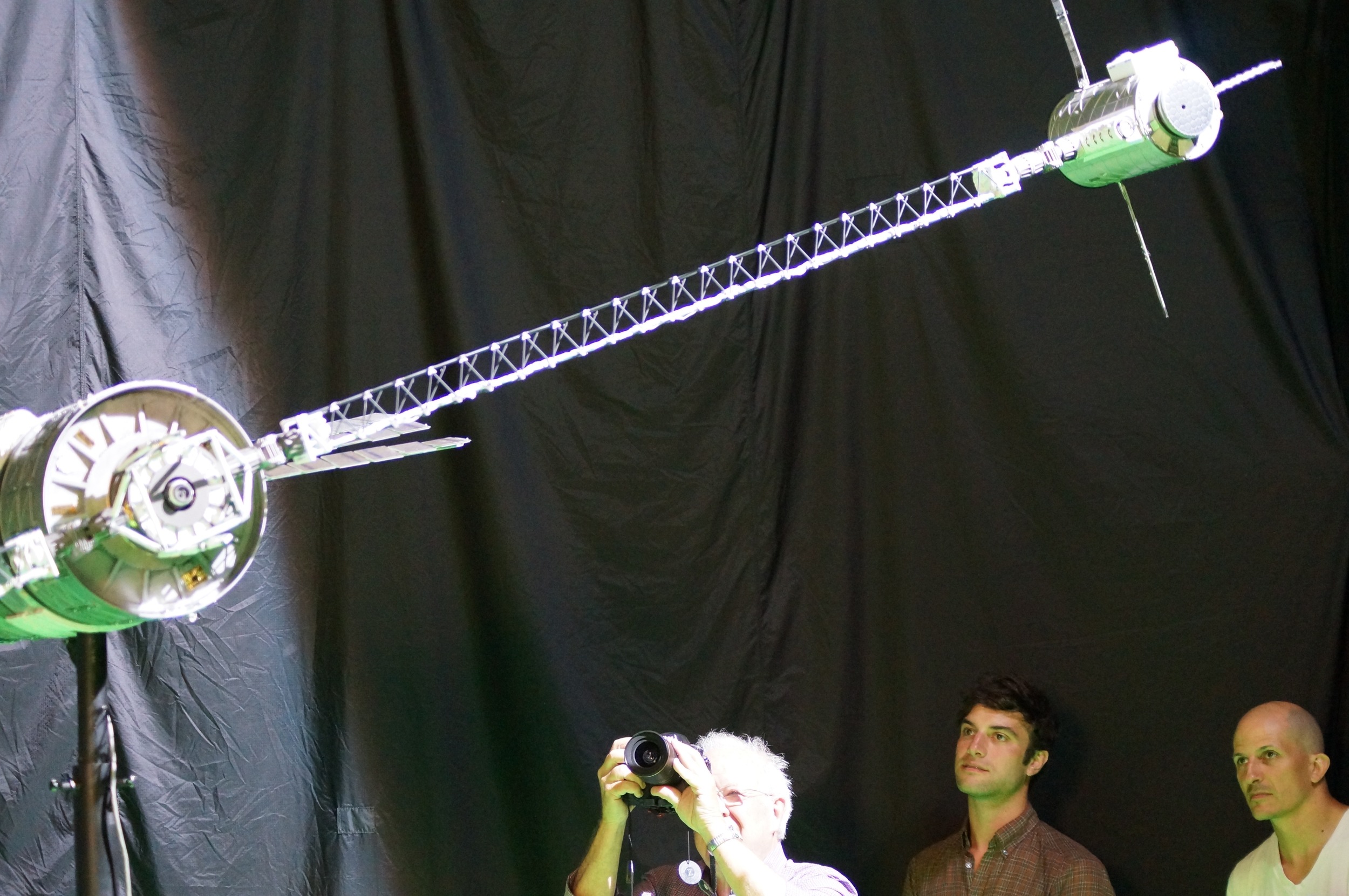

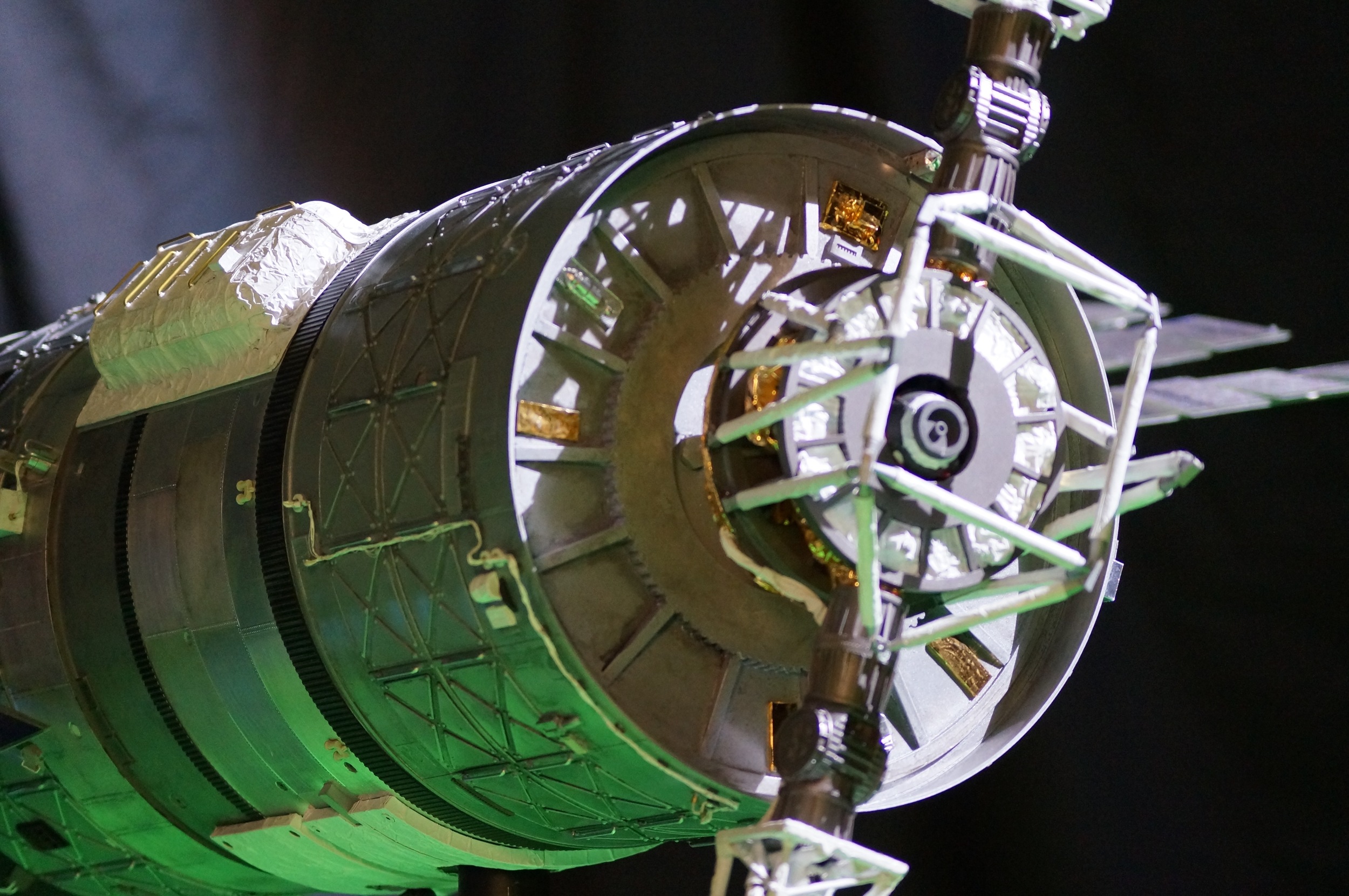

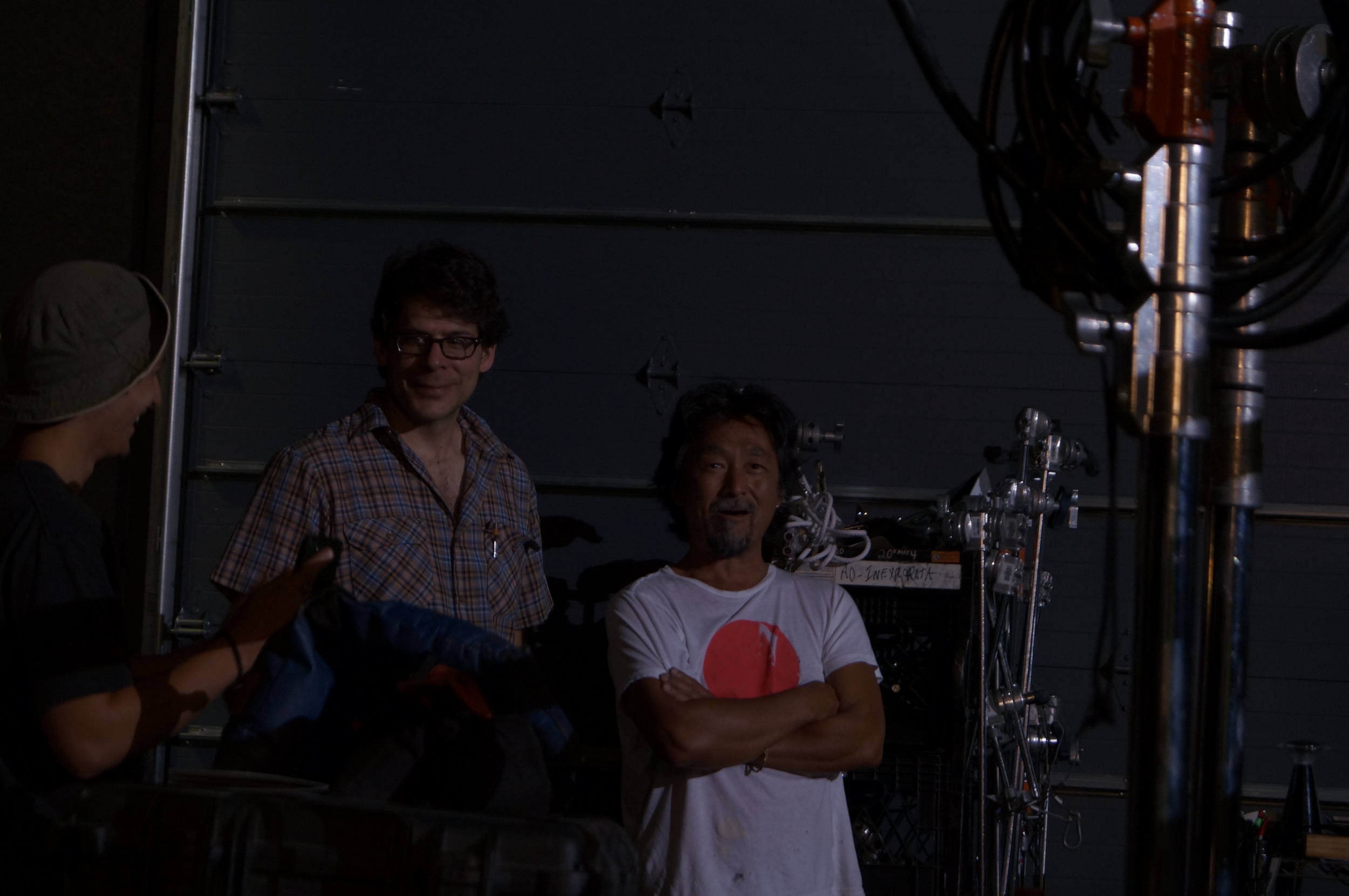

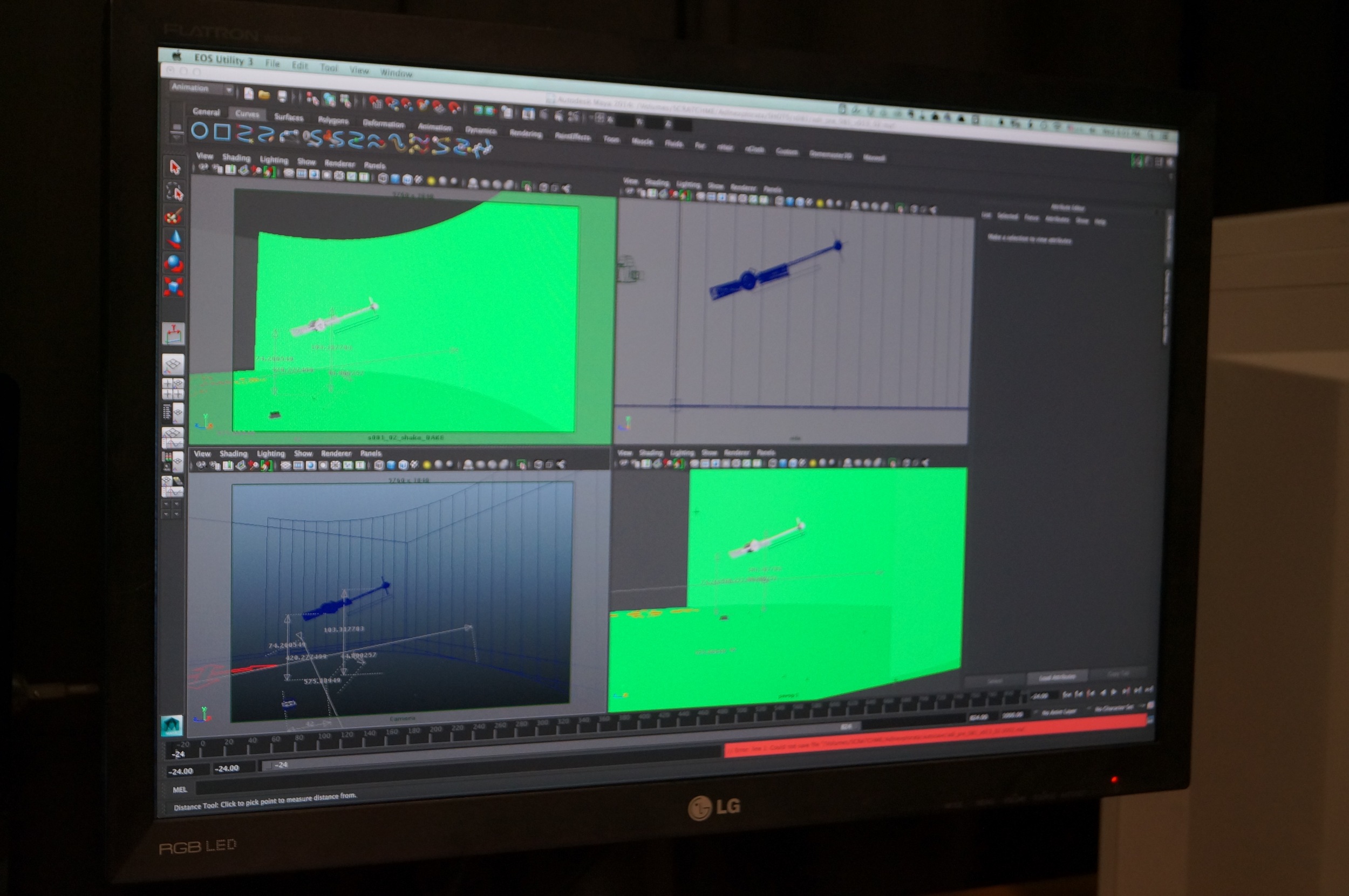

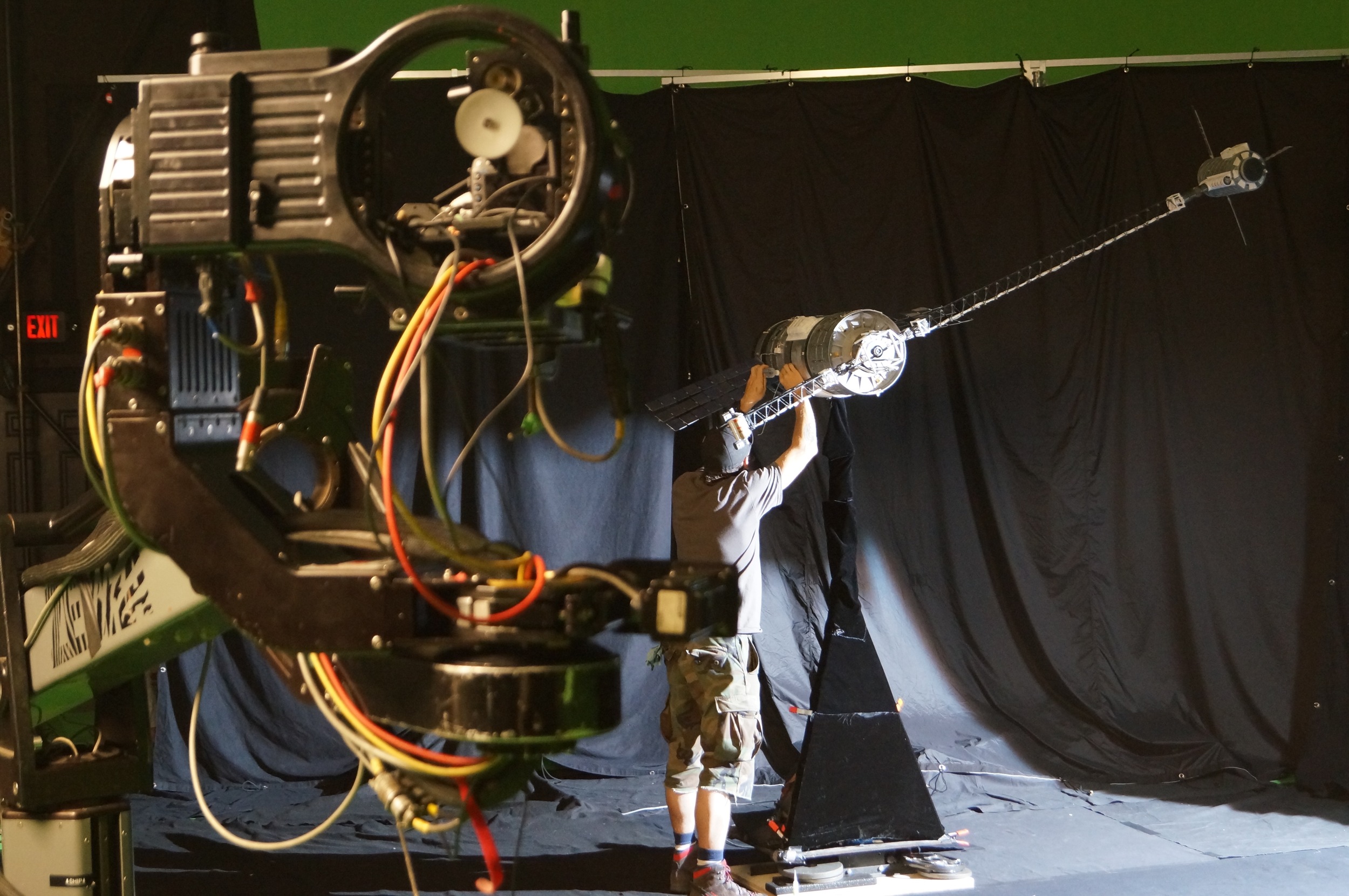

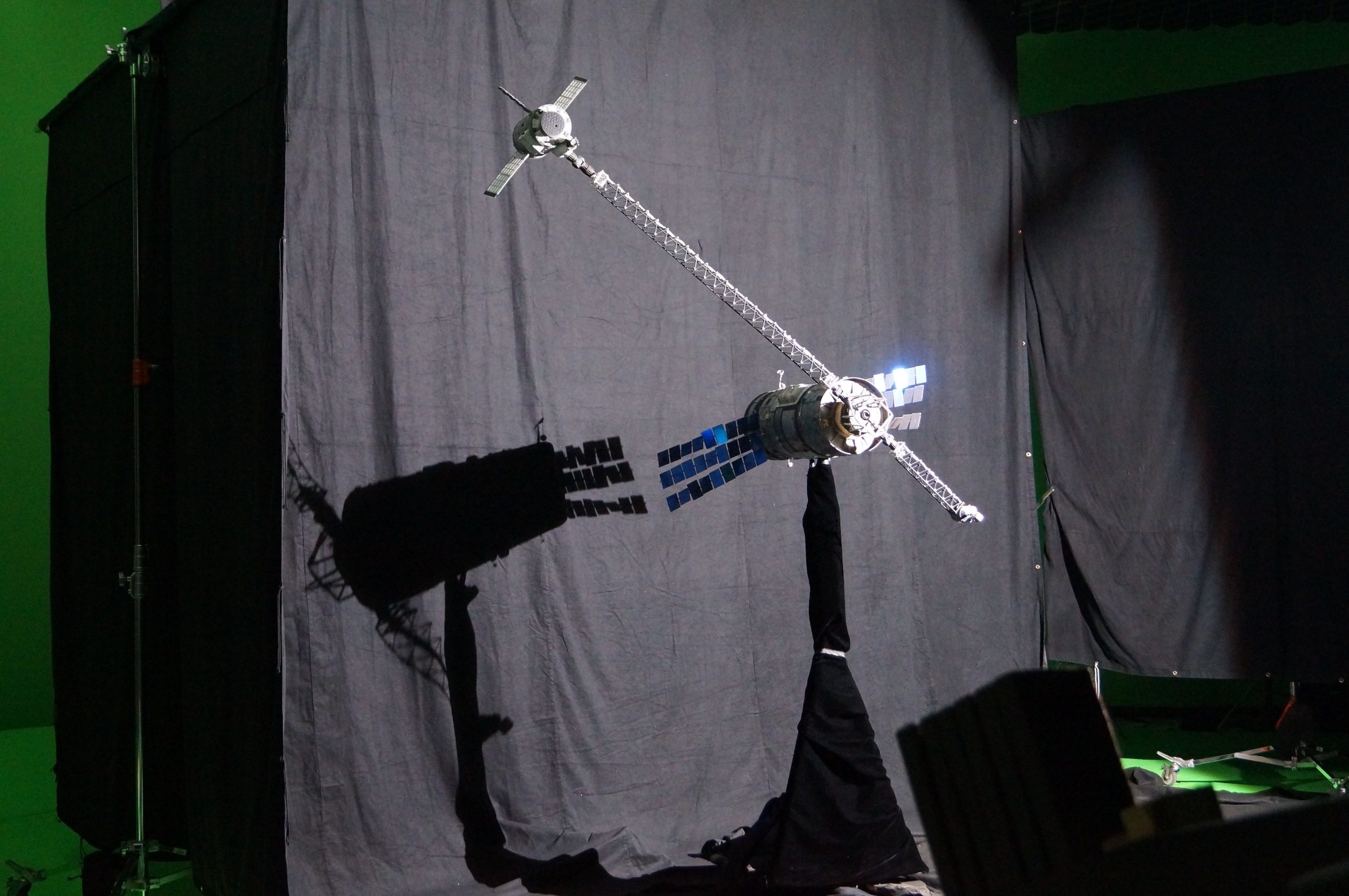

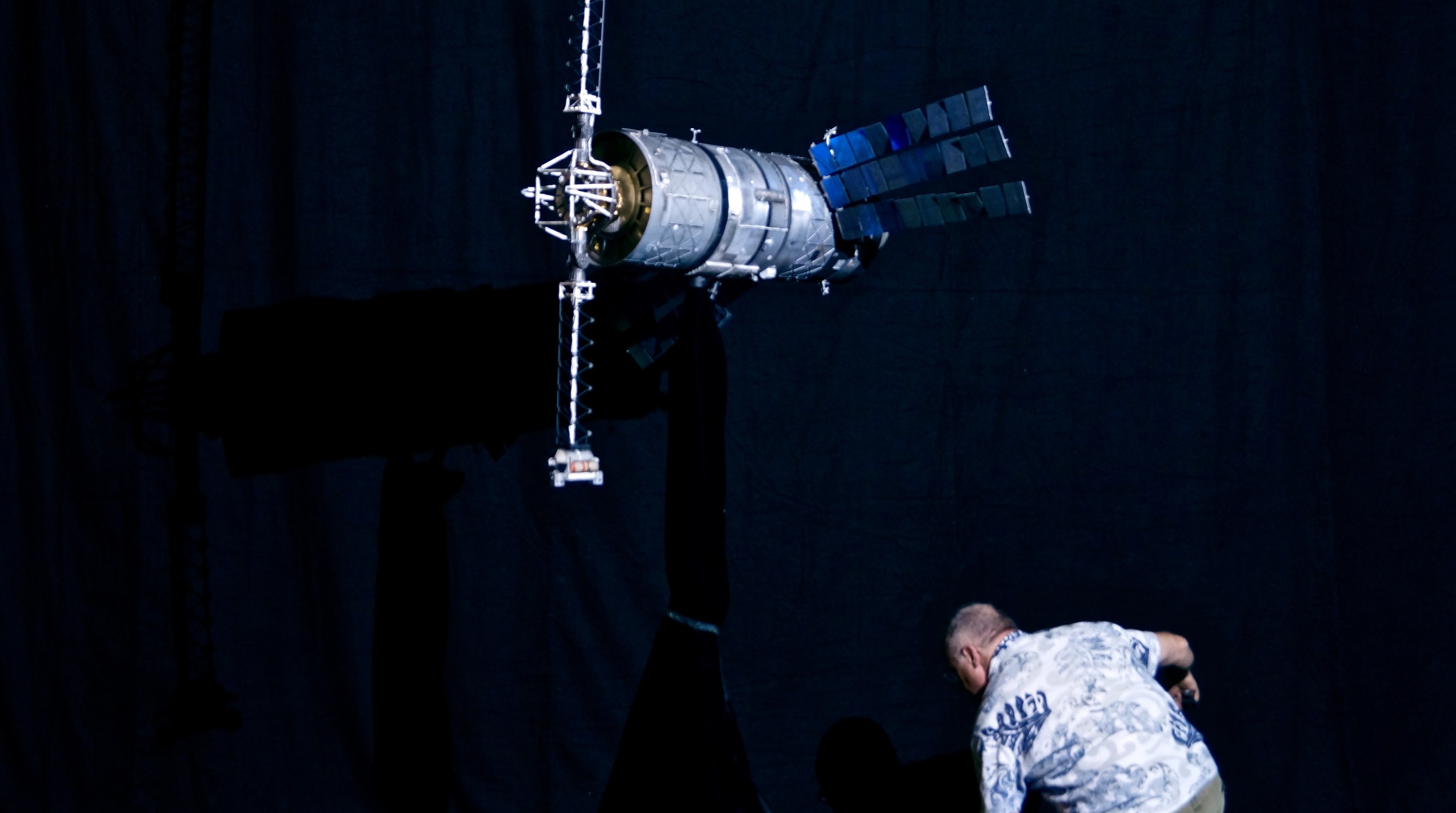

We convinced special effects legend Douglas Trumbull to let us shoot at his studio in the rural Berkshires, and it was amazing to have the advice of the man behind the models for “2001,” “Blade Runner,” “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and many others. Our production designer, Steven Brower, knows more about actual space science than some folks I’ve met at NASA, and he designed a ship inspired by genuine practicalities as well as our speculative fiction. I know it was a real challenge for him—one you wouldn’t have with CGI—to make a ship that was structurally sound. Our hero Zephyr was about six feet long, with an eight foot spinning arm, and it had to actually work. I think you can “feel” the size of the thing on screen, how incongruous it is that this giant machine is floating weightless up there.

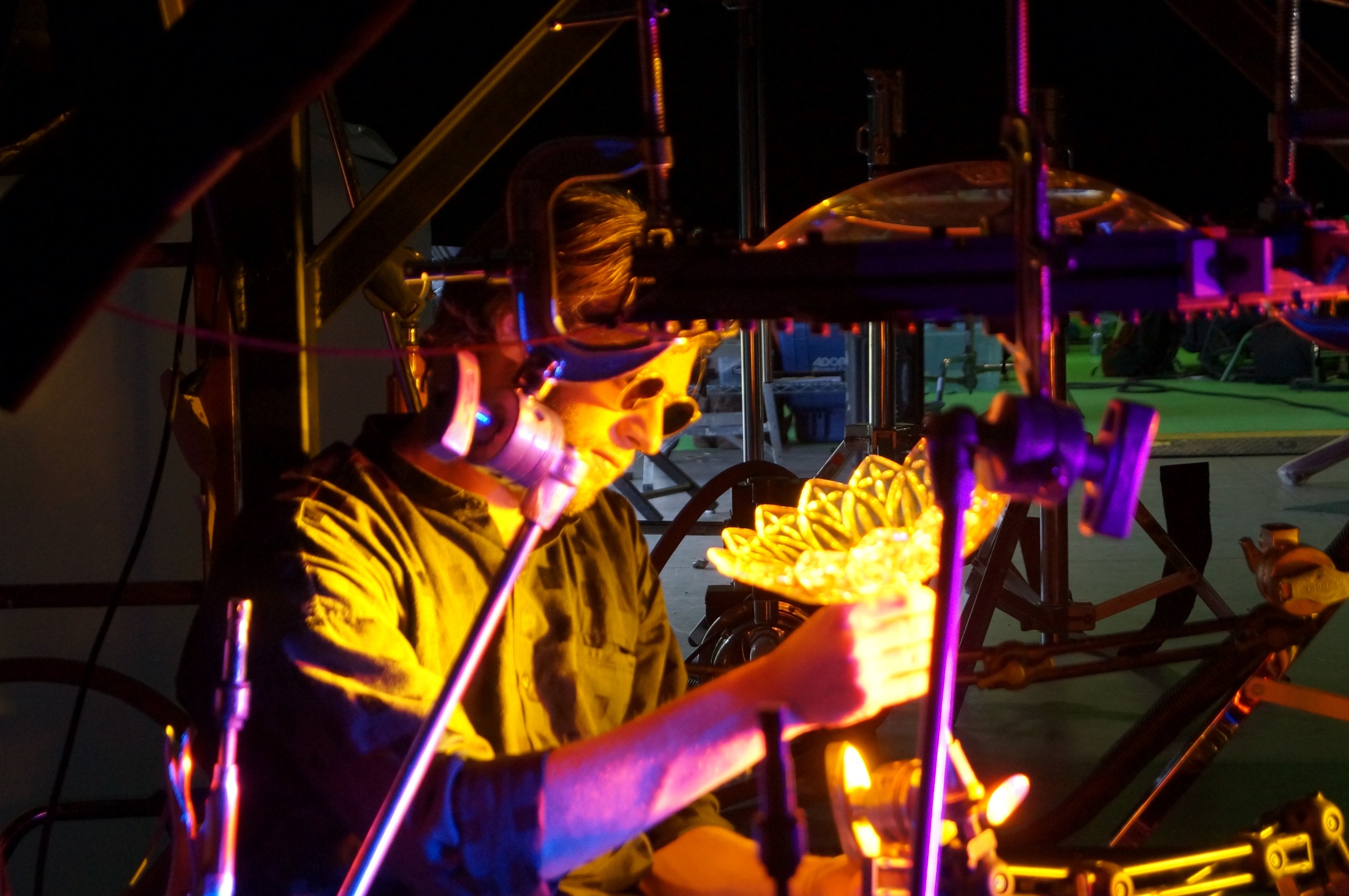

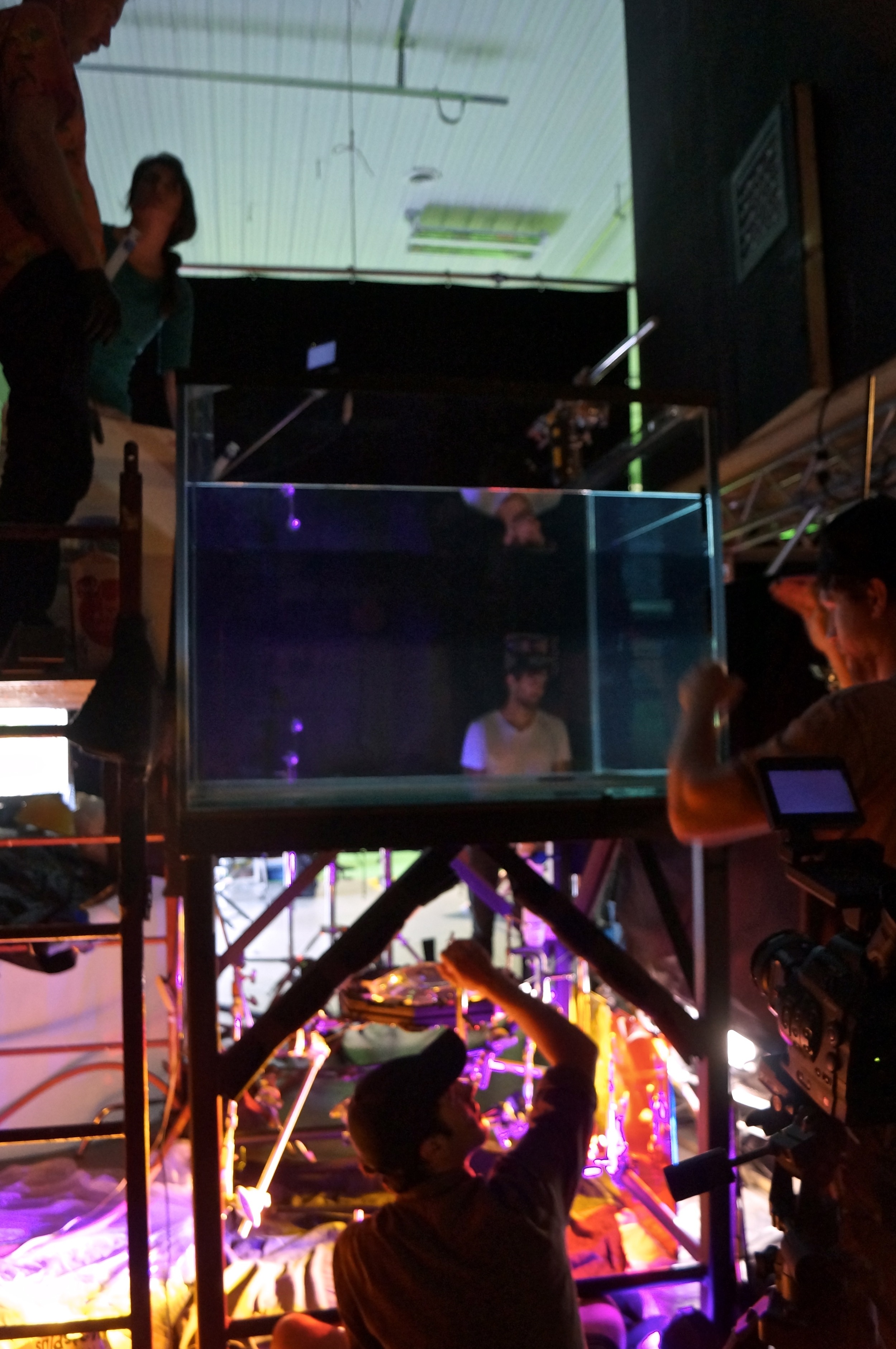

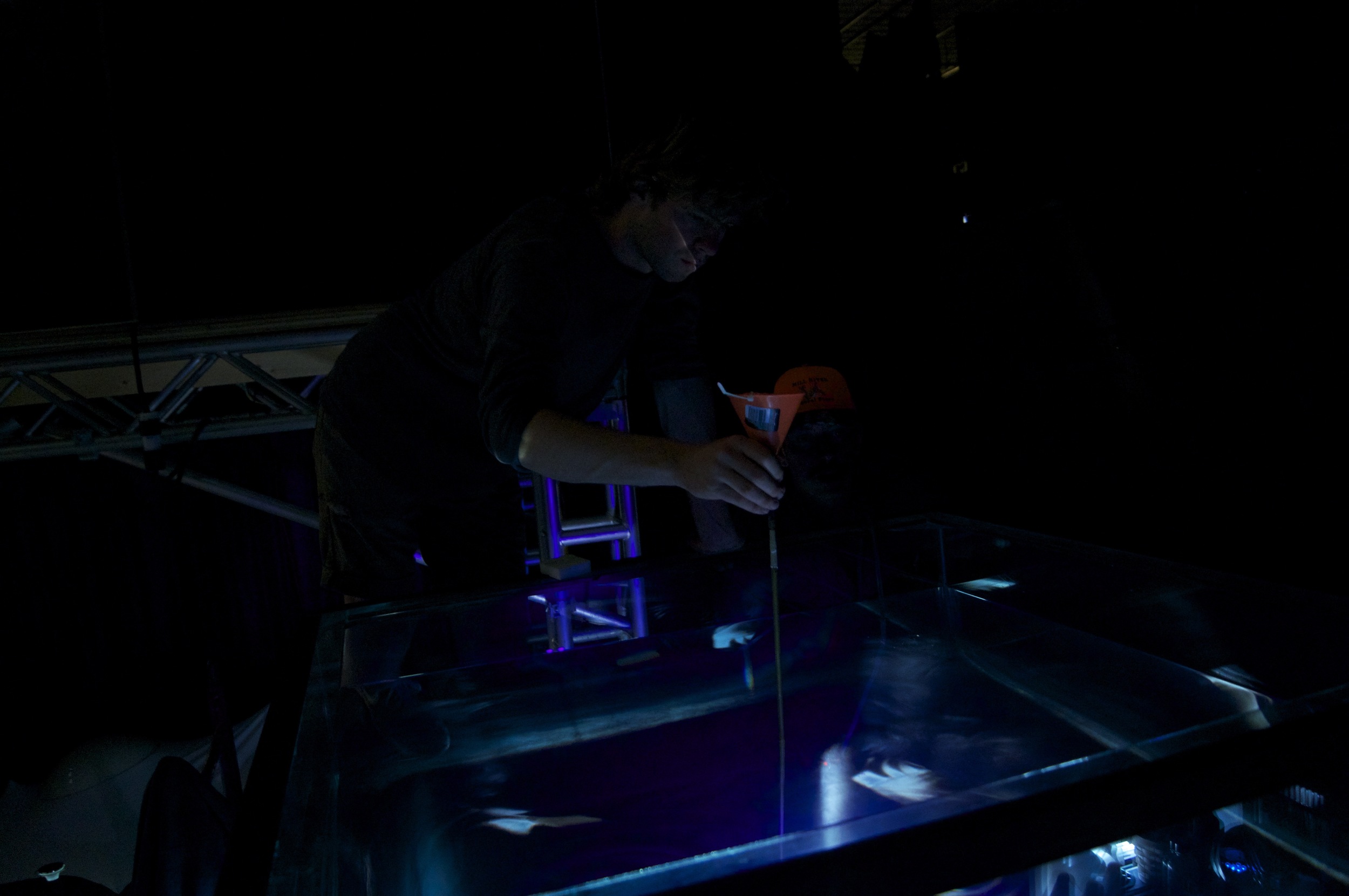

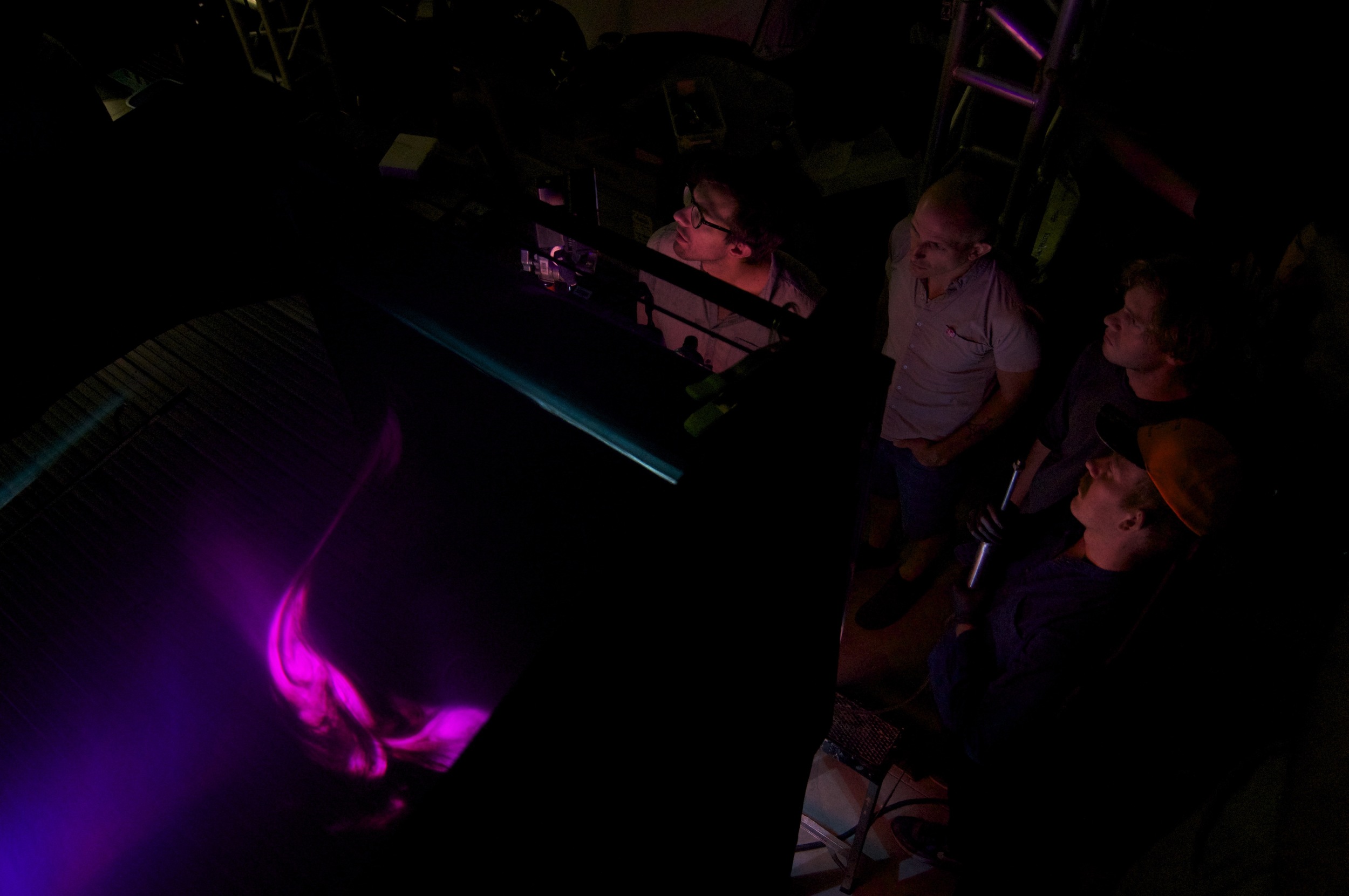

Lastly, I wanted space itself to have a texture. For me personally, the closest I could come to understanding what it would be like to be in the darkness of space would be like being deep under the ocean: it feels empty, but there’s viscosity, and you know it’s teeming with life, much like in space, with radio waves and subatomic particles, space dust and comets, planets and stars. So we shot all this footage in “cloud tanks” filled with glycerin, corn syrup, salt water, into which we would inject dyes and powders and metallic particles. Again, you get these incredible tactile effects that are unique to the materials, and which I think create a subjective mood of growing madness and beauty that is fitting to the story.

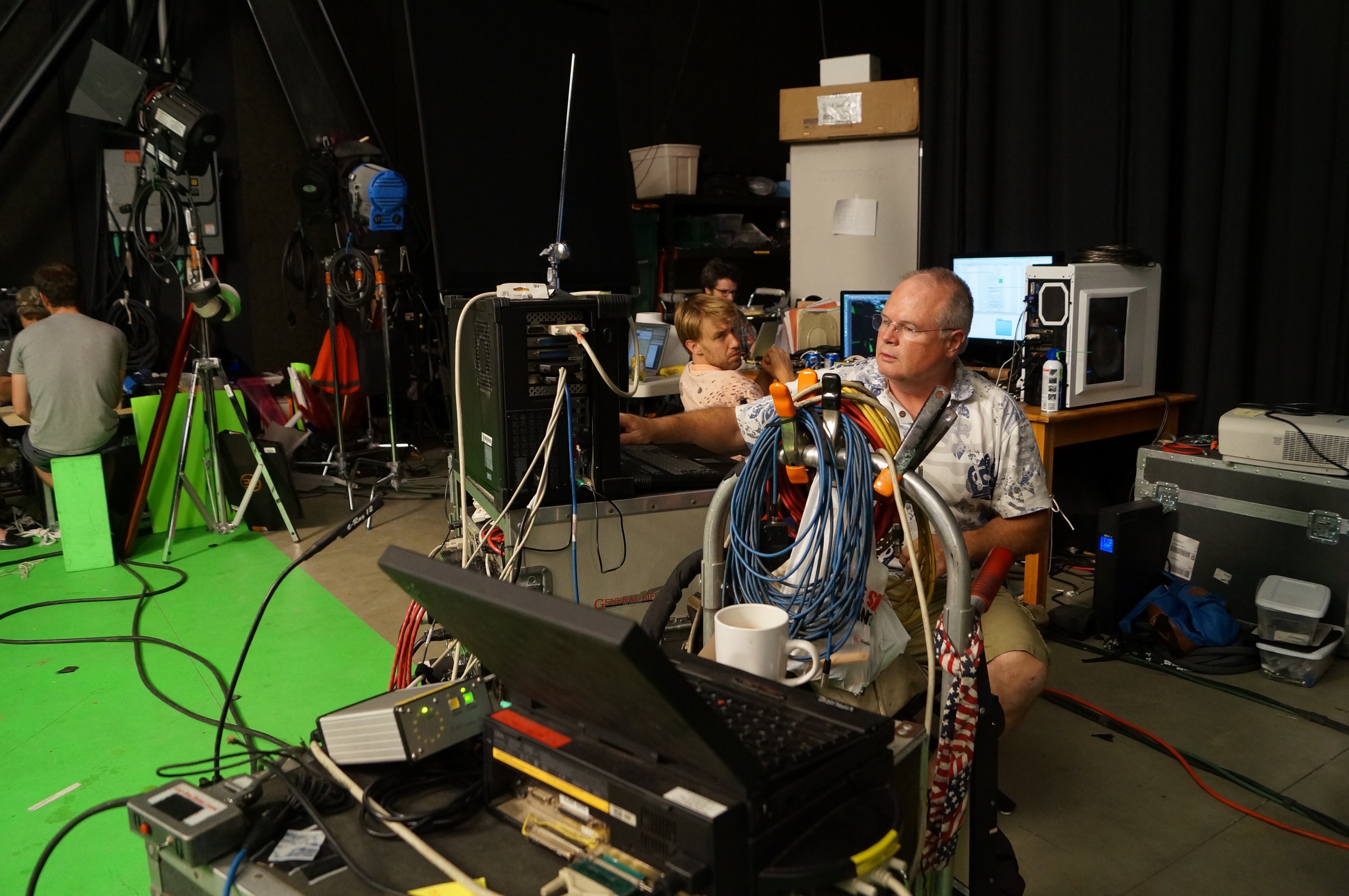

I’m extremely proud of the special effects in the film, and one of the best things about doing them practically was just how fun and creative it was. A huge, stressful challenge, but a joy to achieve.

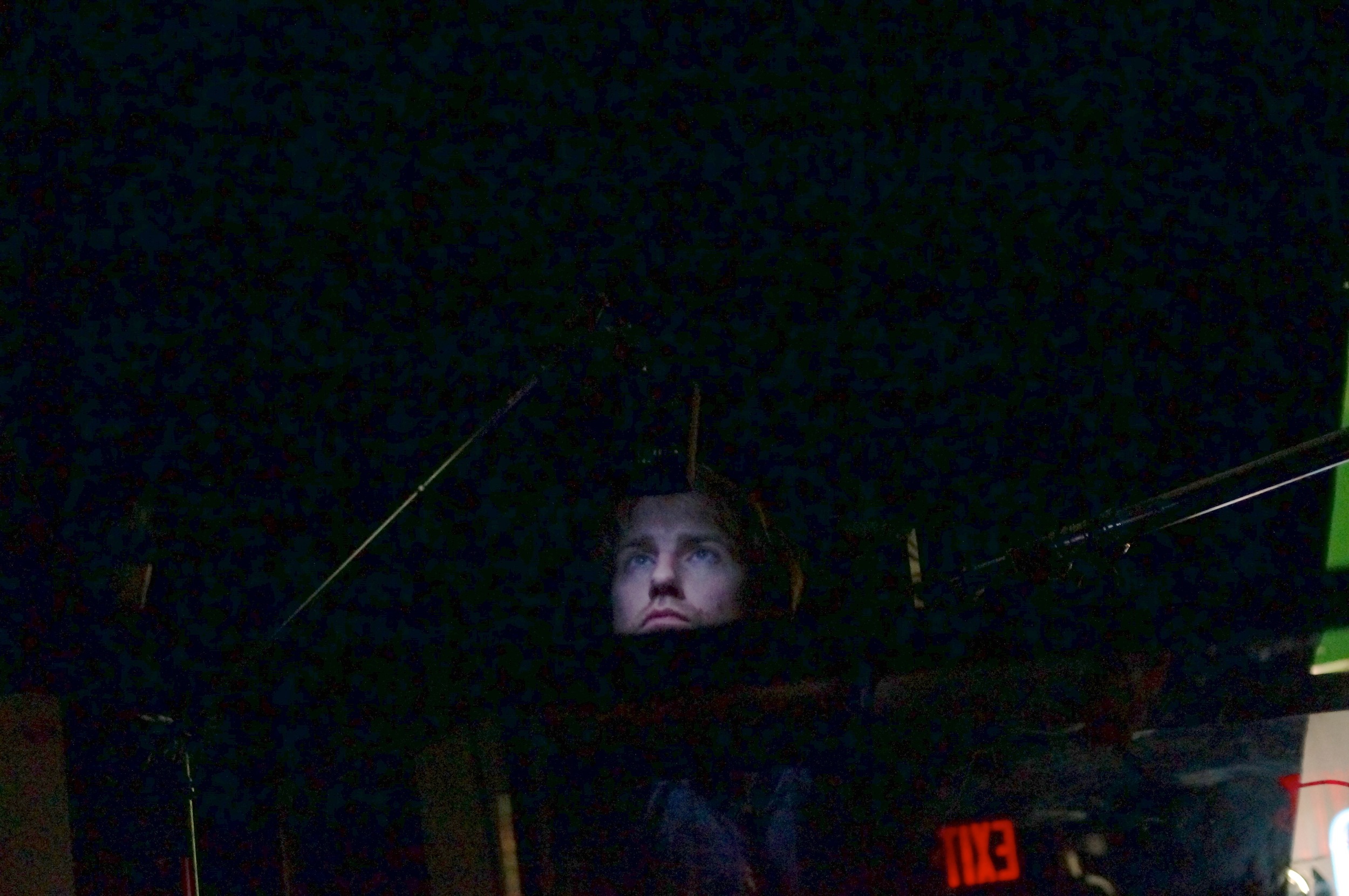

Principle photography was shot on a set in Kerhonkson, NY, deep in the snowy winter. I wanted to get the crew to a remote location to create a "summer camp" feel, where everyone was living together, eating together, bonding and focused solely on the film. Being in a big empty warehouse for three months of set construction and one month of shooting also created an effective atmosphere of (happy) isolation; like the character, we were off on our own, having a crazy adventure, trying to survive.

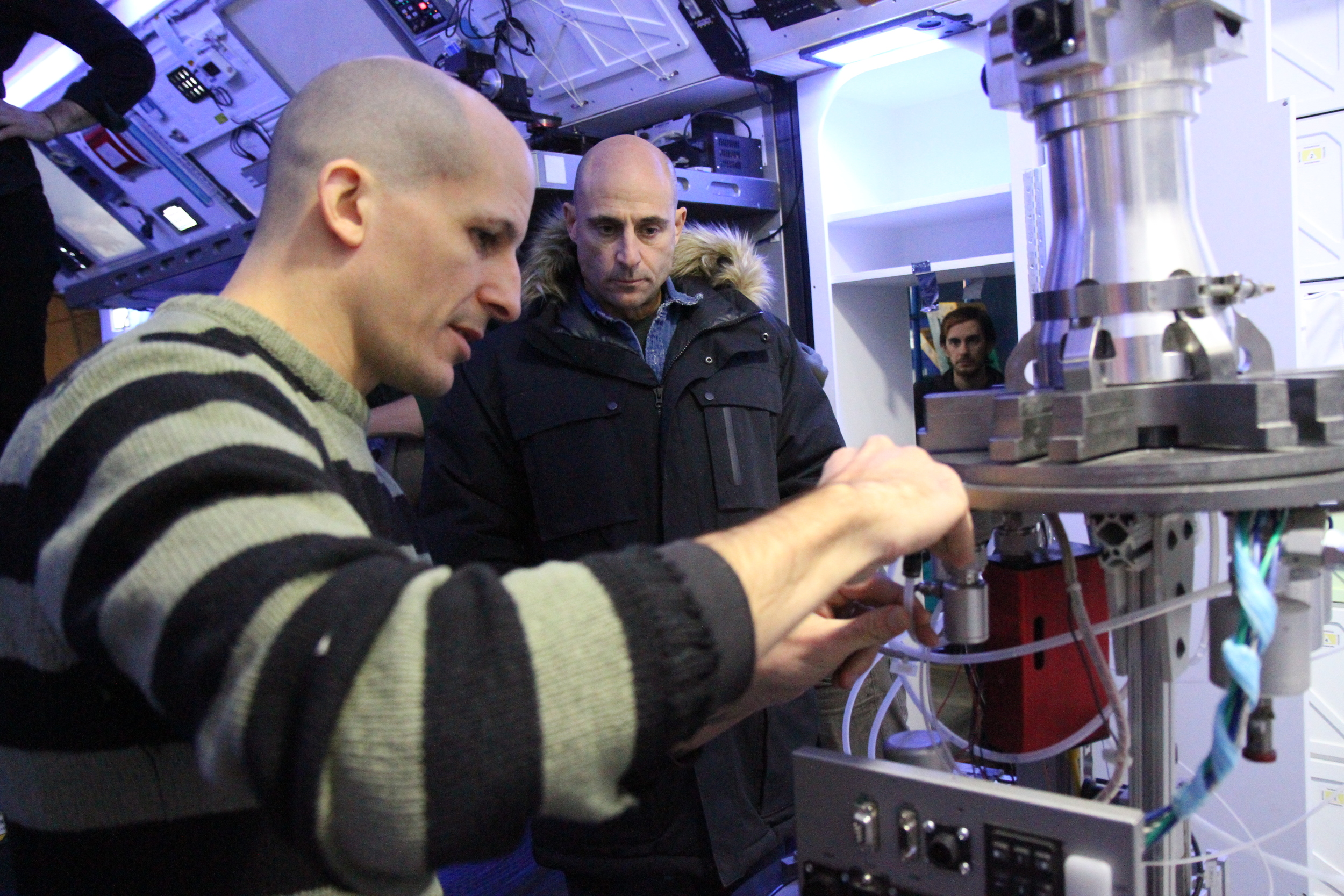

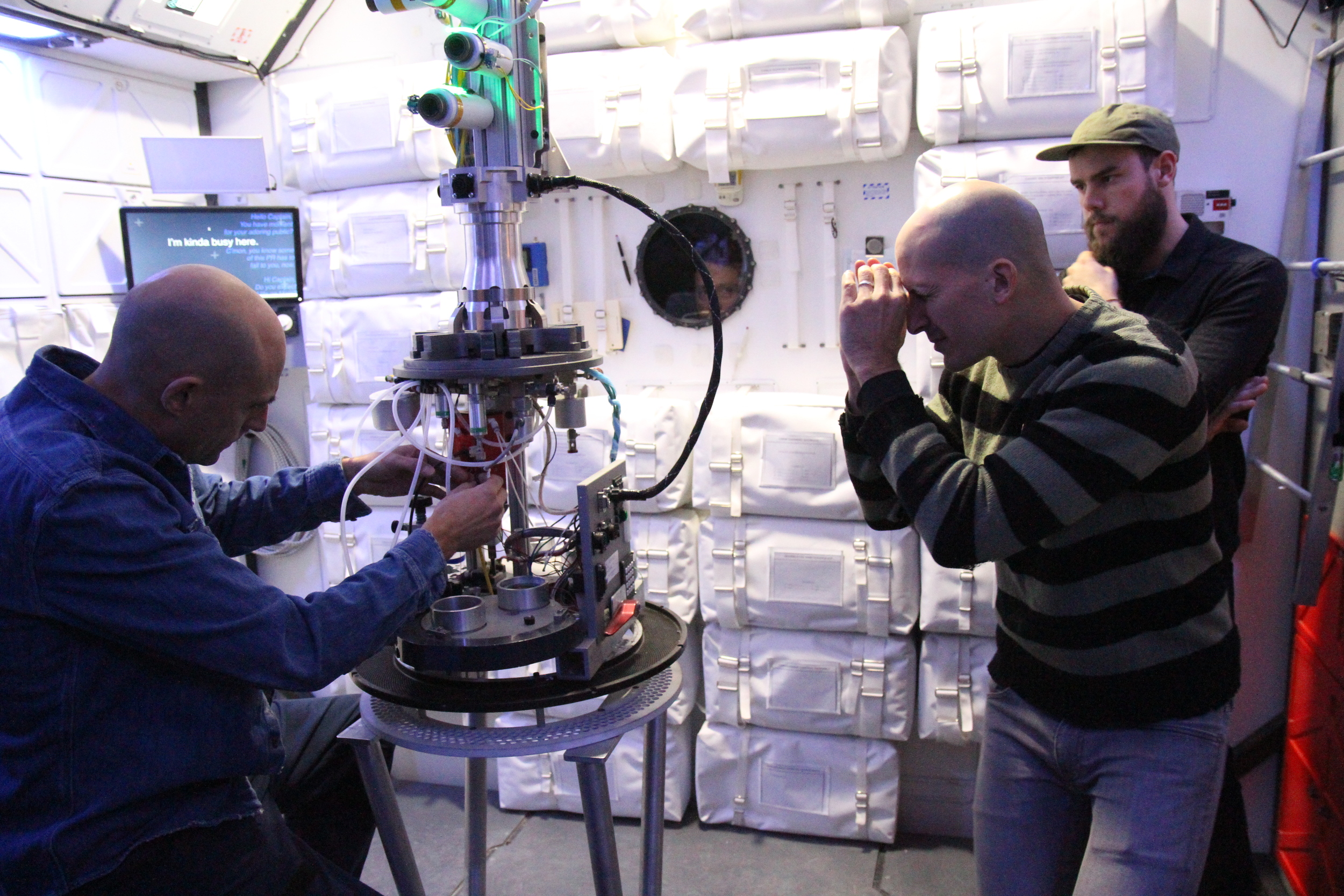

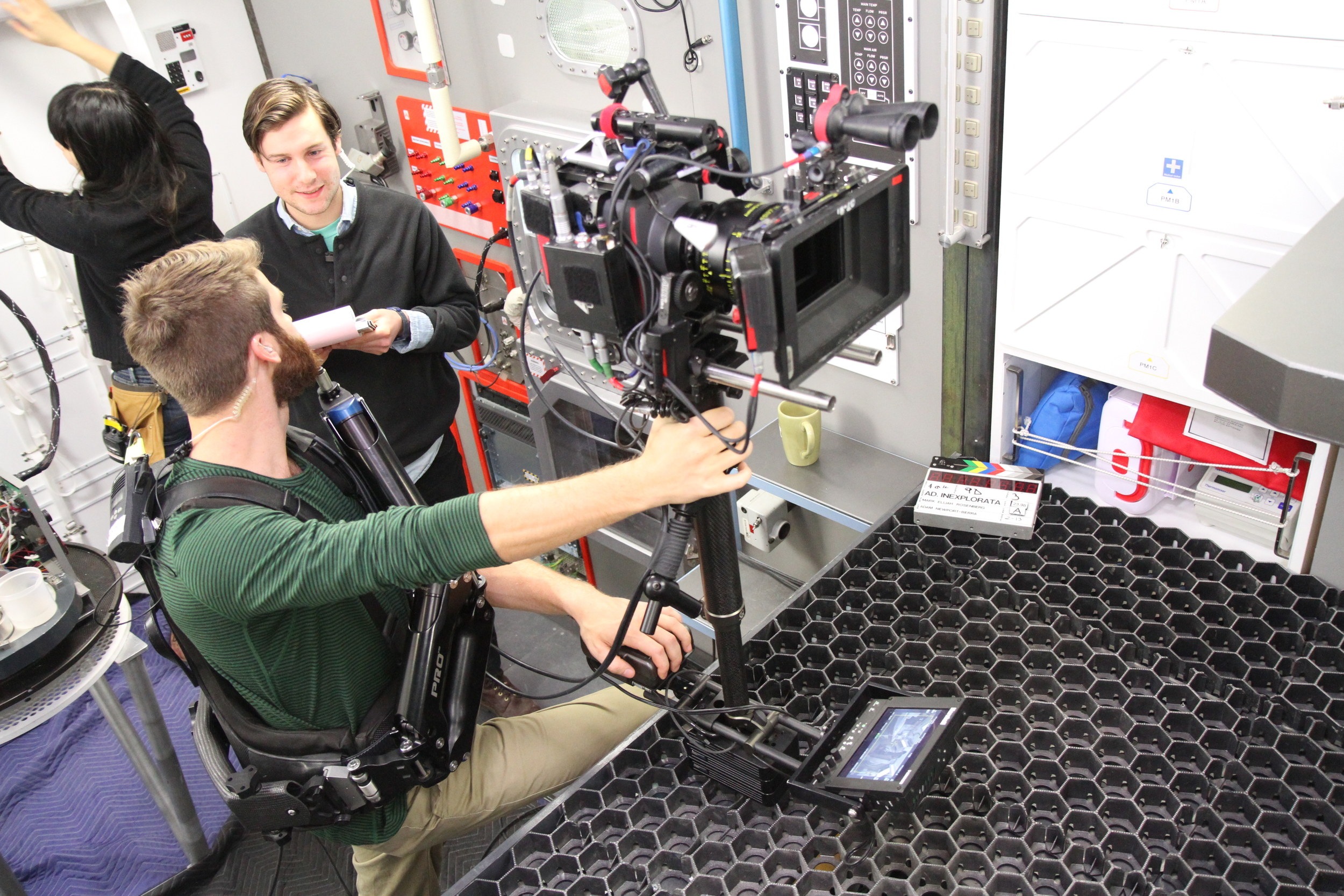

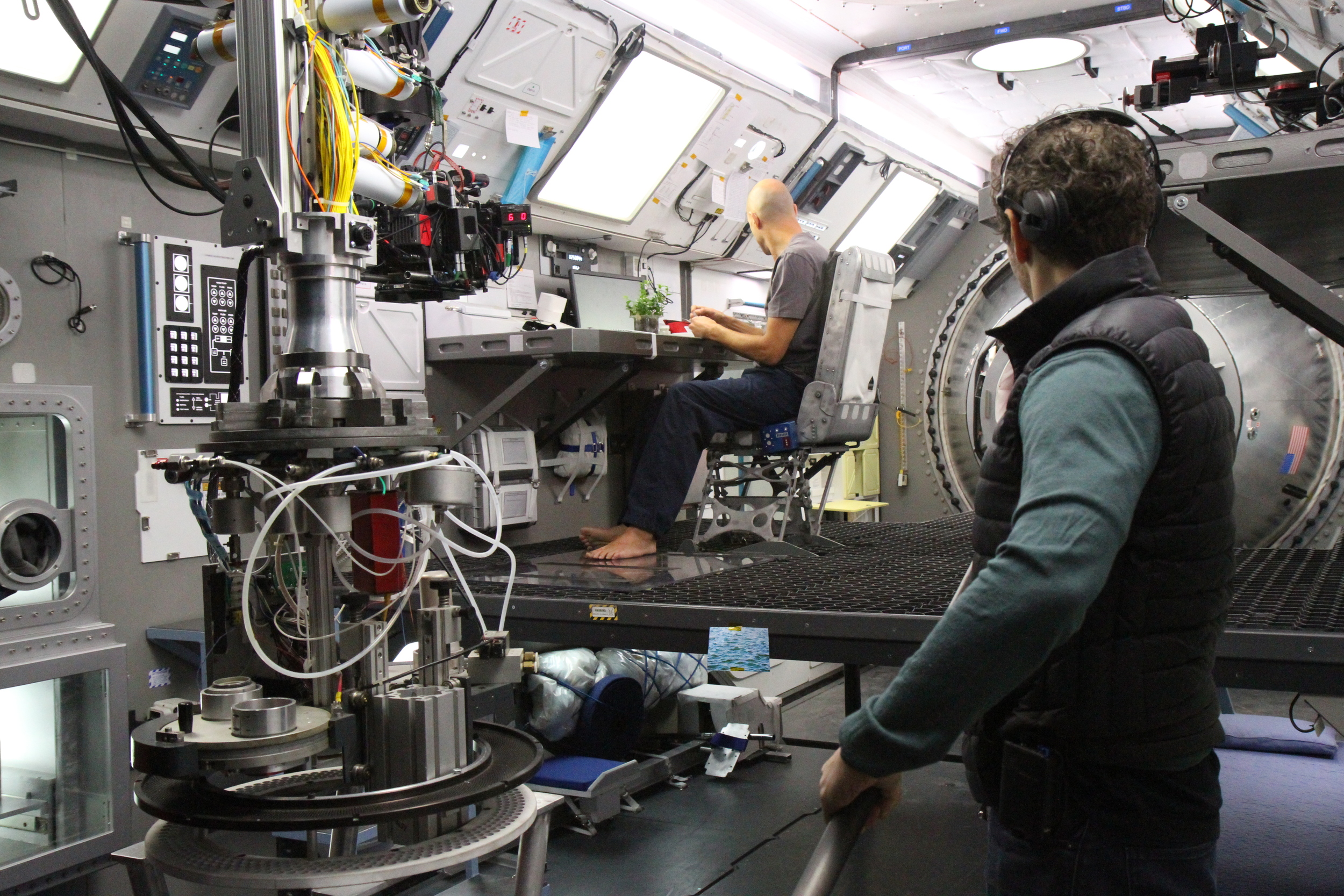

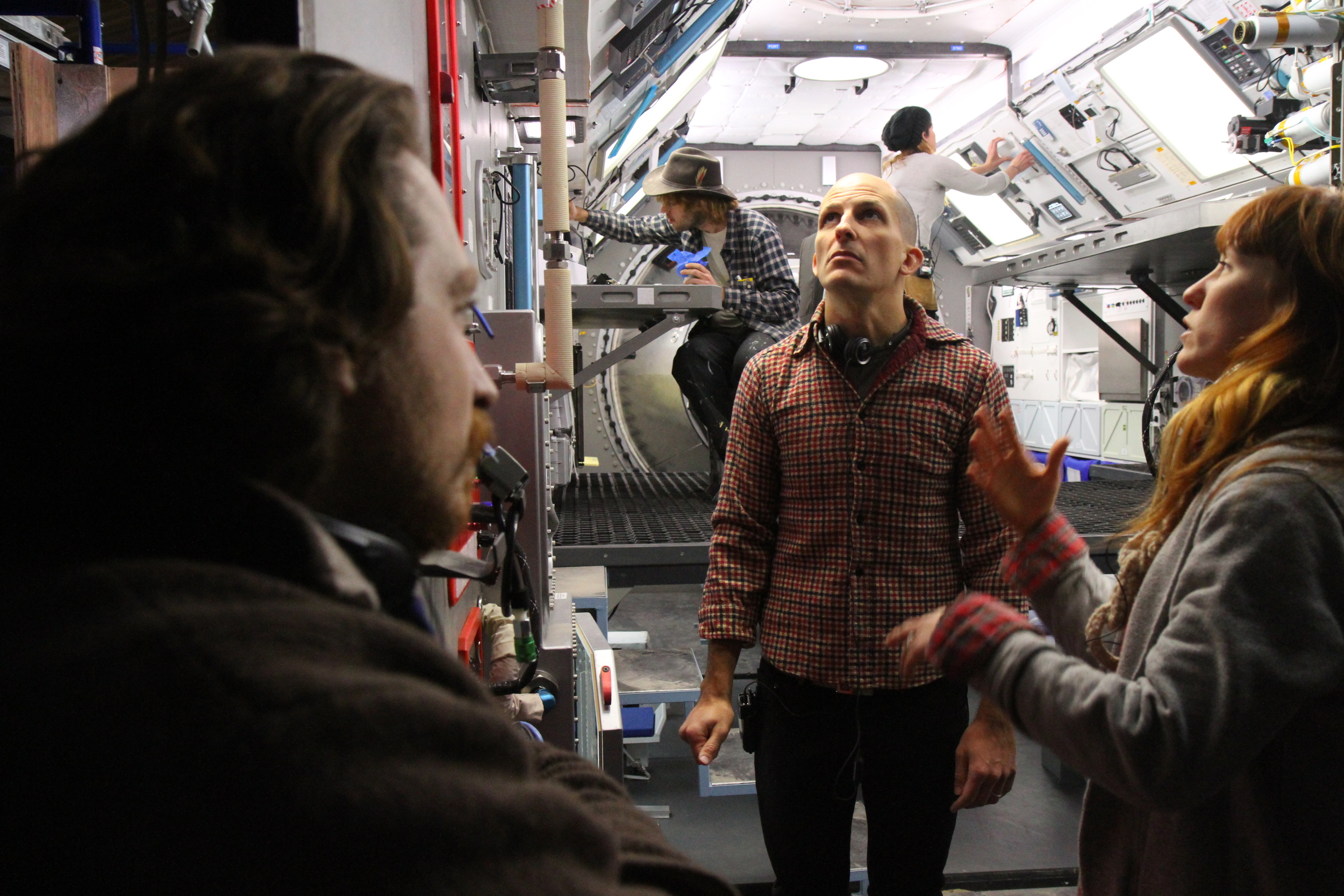

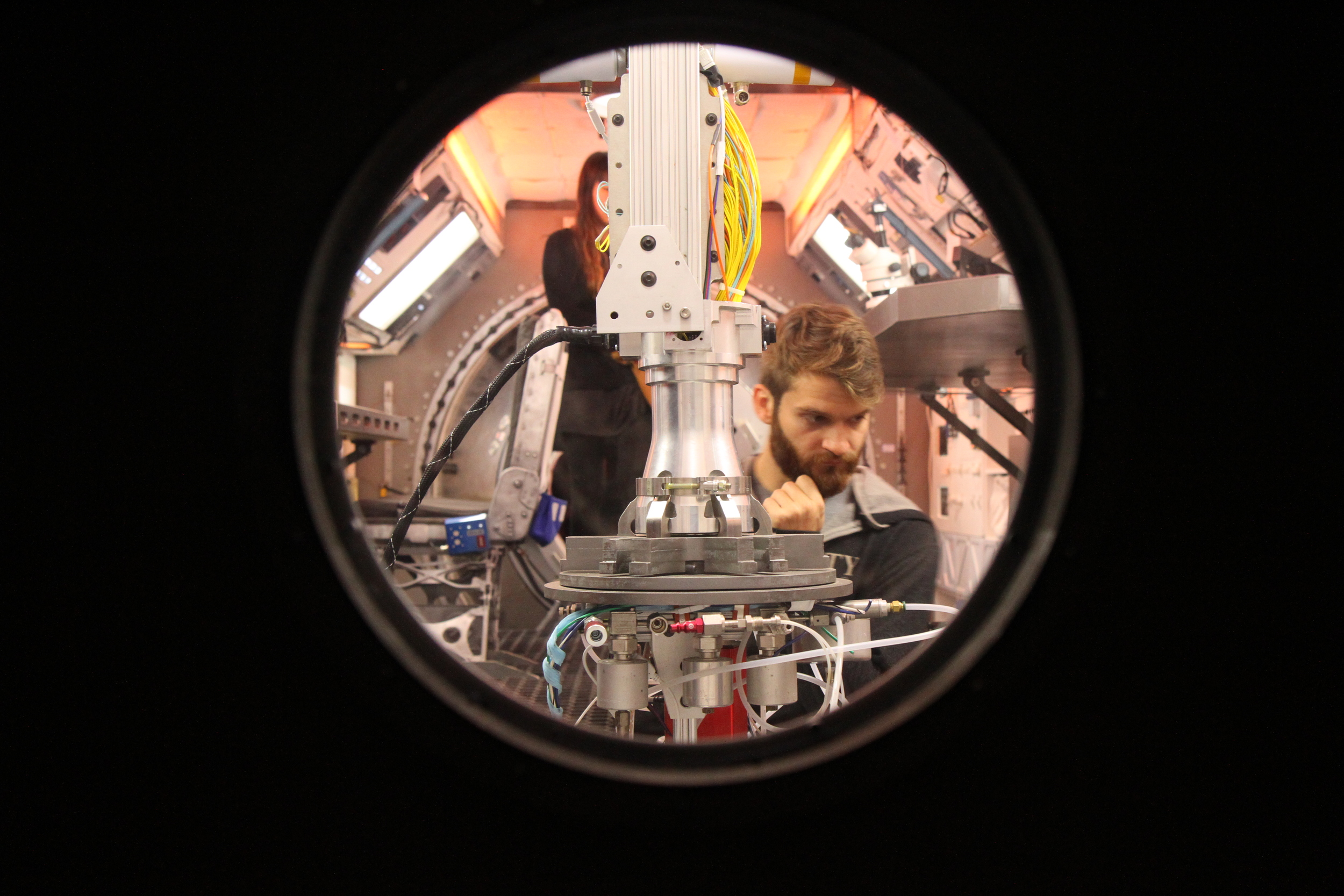

The spaceship set, The Zephyr, designed by Steven Brower, was 12 feet wide and 36 feet long, plus the "lander" capsule. It consisted of three 12' x 12' boxes, with removable walls so we could move the camera in and out. When the walls were all in place, the only entrances were through the ship's "closet" (which we called Narnia). The set was fabricated using a wild combination of airplane parts, medical detritus, random junk, and original pieces made just for the shoot. The crew did an amazing job making a nuanced and realistic ship on a limited budget. The Zephyr is a character in the film, and its evolution through the film is crucial to the narrative.

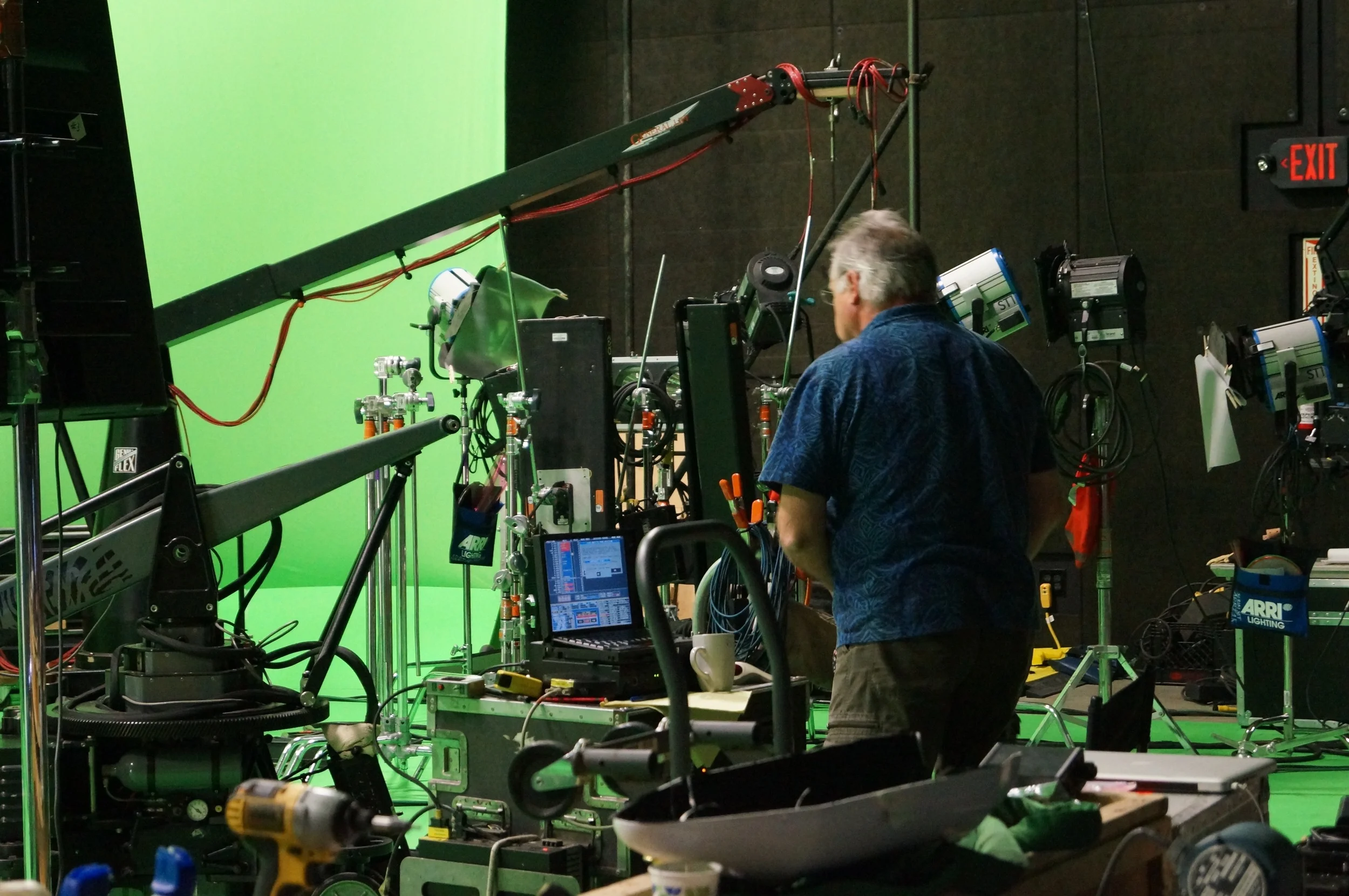

Our DP, Adam Newport-Berra, did a brilliant job finding a variety of ways to frame the ship throughout the film, so there's always something new to see. We shot a lot of the film on a crane, extended into the ship and floating through it. All of the lighting was practical, with a design by gaffer TJ Alston that was controlled via computer. It was our idea that for the sanity of the character, the space agency would design the ship to have a diurnal lighting cycle, so we could set different scenes at different times of day and evoke different moods.

All FX photos by Danny "Starfield" Garfield. All principle photos by Irwin Seow.